Toby Morrison started working in underground coal mines in 1947. Those were the days when mateship, perseverance and solidarity became words we would forever associate with underground coal mining.

Toby was born on a farm in Boggabri in 1930. Ten years later the family moved to Gunnedah which is where Toby still lives to this day.

There were not many opportunities for work in those days as the country was coming out of the Great Depression, so when Toby left school at age 14, he started rabbiting with his father.

“Catching rabbits got a lot of families through rough times. You would sell the pelts to Akubra and sell the meat.”

When Toby turned 17, he started working at Preston Extended Mine.

“I was sick of rabbiting. My older brother had a job at the mine so one Saturday morning when we knew Harry Thomas the mine owner would be in town, my brother took me up to Town Hall to meet him. Harry told me to start work on Monday.”

That’s how simple the interviewing process was in those days. Toby’s brother vouched for him, so Toby got the job. What was also simple was the induction process – that is there was none.

“On the first day they said here, put this helmet and belt on and off you go and they sent me down in to the drift.”

The drift is the tunnel entrance that leads from the surface to the coal seam and Toby’s first job was to hook up and unhook the skips which were on a wire rope pulley system powered by steam driven engine.

“I was frightened, I had no idea what was going on. The skip would come roaring down, it was so fast. Scared the hell out of me at first.”

Working eight hour days, Monday to Friday, Toby earned a wage of $1.75 per day.

“It was good money, especially for my age. It was by far the best paid job available.”

It was also by far the most dangerous.

There was no electricity, every job was done by hand, it was loud, dirty, dark and wet. Injuries were common and unfortunately lives being lost were common too. While Toby was working there, four miners lost their lives.

“You always had to watch out. I was first on the scene when two blokes were killed.

“You just had to push it aside and go back the next day.

“It was hard work, but you got used to it. I loved my pick and shovel days. When you shovelled the skips, you would have two blokes working together. The more you produced the more money you made.

“You had to be fit. None of the guys would have any problem passing a medical – not that there were medicals back in those days.”

While the money was good, that wasn’t what Toby most loved about the job.

“The workforce was solid. Everyone was your mate. You stuck up for one another and looked after each other.”

Toby spent 35 years in the industry and there was no such thing as job security.

“There were so many strikes, always around working conditions and safety. Things like bad air, or sometimes you would have a mine manager that would try to make you work even when it was dangerous.”

In 1983 Toby led a strike that had an enormous impact on the coal mining industry.

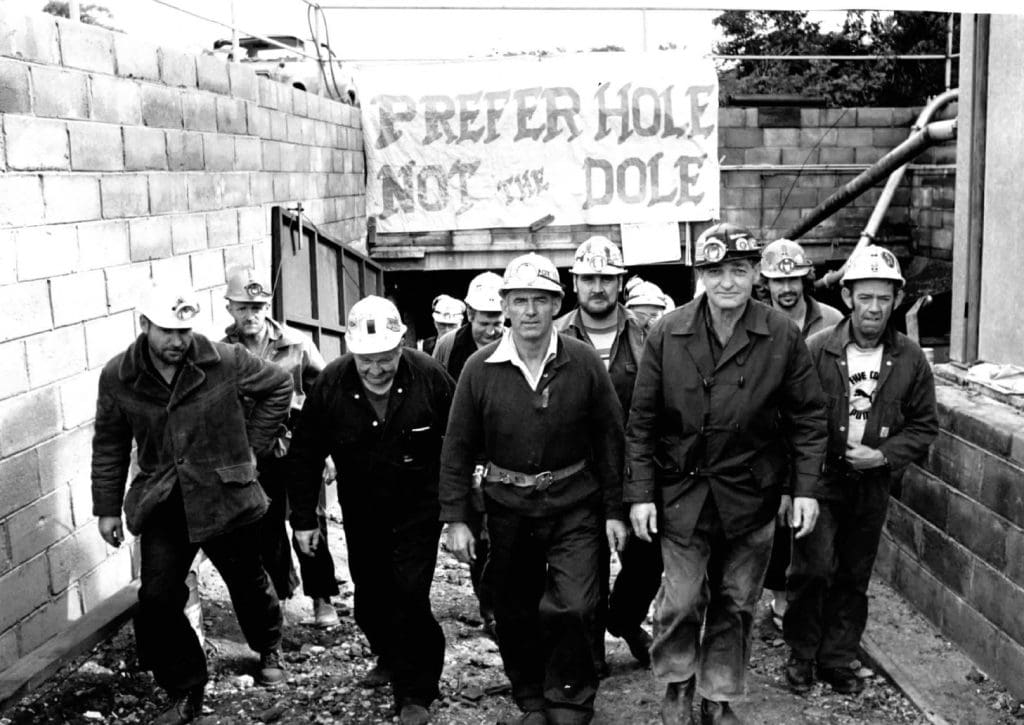

The protest began when the Preston Extended Mine sacked 83 of its 106 mineworkers with no warning. At the time, the mine was owned by RW Miller who also operated the Mt Thorley mine in the Hunter Valley, so as a consolation they would keep nine workers on at Mt Thorley. Toby was one of those nine, but instead of taking the easy option he rallied the miners and began a ‘sit-in’ in the underground mine.

Sixteen miners began the strike. After two had to return to the surface for medical and family reason the remaining 14 men became known as the Preston 14.

The mine owners tried many ways to end the strike, threatening to turn the power off, which would leave the miners in darkness, and even more dire, stop the fans that supplied the ventilation to the mine.

“I got in touch with the Seamen’s Union who were backing us, and they got those lights back on pretty quick. The Seamen’s Union could apply pressure because they controlled the coal ships.”

The Preston 14 received a lot of support from the Miners Federation Lodges but that was only the beginning. Unions from across the country and even in other parts of the world sent in telegrams and donations.

However, while support came in from far and wide, not all in the community were happy about the sit-in.

“Not everyone in the town liked what we were doing, and they found ways to show it. We had a barber from town come out to cut our hair. Afterwards the townspeople starved him out and he ended up having to close his shop and leave town.”

But overwhelmingly the support was positive and without the many volunteers Toby said the strike would not have happened.

“Wives and family members would bring food and water to the tunnel mouth, and we would come up and eat and then go back down.”

Finally, after 55 days spent underground – the longest industrial action of its kind in Australia’s mining history – the mine owners conceded.

Every miner who had been fired received a severance package and 53 of the sacked workers got their jobs back.

The strike, which had garnered worldwide attention, also led the NSW Government to take action on the orderly development of the coal industry and the retention of coal jobs through the restructuring of the Joint Coal Board.

On 19 May 2022, a monument to commemorate the 1983 Preston mine sit-in was unveiled in Curlewis. A tribute to the Preston 14 and a permanent reminder of the true meaning of mateship, perseverance and solidarity.