In February 1893, the Eclipse Colliery at Tivoli, Ipswich, owned by John Wright, was the epicenter of a disaster that marked one of Queensland’s darkest moments in mining history.

Amidst a series of devastating cyclones that caused unprecedented flooding across South East Queensland, the Eclipse mine suffered a tragic event that claimed the lives of seven miners.

These miners while hewing coal for the pumping station at Mount Crosby (among other places), included the owner’s sons, Thomas and George Wright. This incident is not merely a footnote in the annals of mining history but a profound narrative of human tragedy and resilience.

The flooding of the Bremer River, particularly severe due to the cyclones, resulted in water forcefully entering the Eclipse Colliery’s tunnels. On February 4, as the community grappled with the wider impacts of the floods, the miners at Eclipse were engaged in a routine transition of work from Tunnel No.1 to No.2. Unbeknownst to them, this day would turn catastrophic as water inundated the mine, trapping and ultimately drowning the miners in a cold, merciless grave beneath the earth.

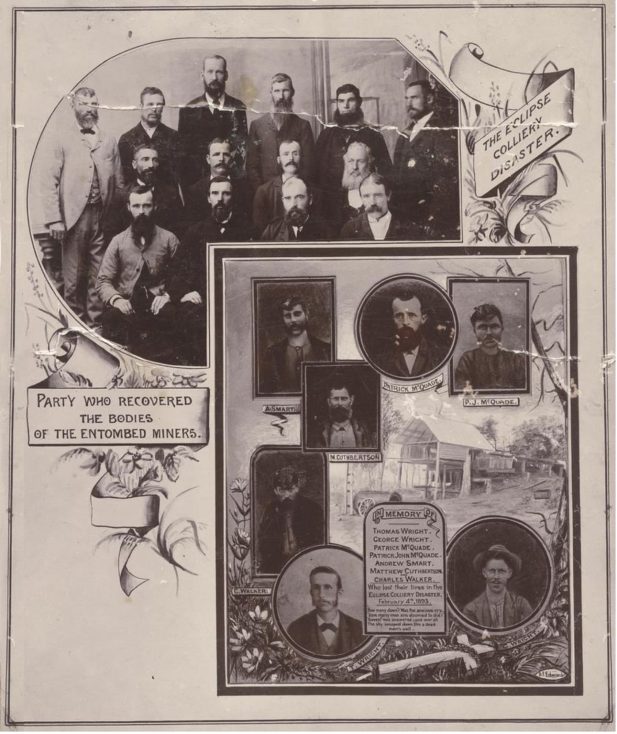

Rescuers played a pivotal role in the aftermath of the Eclipse Colliery disaster. Among the volunteers were Robert Miller, A. Nimmo, John Eadie, Charles Sollitt, David Campbell, John Stafford (the mine manager), Robert Palmer, Andrew H Campbell, Fryer (the mining inspector), P. McInally, J. Ainsworth, J.D. Campbell, and A. Muir.

These men embarked on a hazardous and emotionally taxing mission, venturing into the mine’s flooded and unstable tunnels. They faced uncertain and dangerous conditions to recover the bodies of their fellow miners, demonstrating extraordinary courage and a selfless commitment to their community.

Their mission was not merely a physical effort but an emotional journey, as they worked tirelessly, aware of the families’ anguish as they awaited the return of their loved ones.

One of the most poignant stories of the rescue effort involves David Campbell, who, despite the personal risk, persisted in the search for his fellow miners. His determination was driven by a promise made to the families that he would bring their loved ones back for a proper farewell.

The technical challenges were immense, the rescuers had to navigate through debris, manage the risk of further flooding, and contend with the psychological toll of operating in such a grim environment. Despite these adversities, their unwavering resolve stands as a testament to the human capacity for compassion and sheer resilience in the face of tragedy.

The disaster left behind six widows and saw twenty-five children fatherless, highlighting the perilous nature of coal mining, an industry intertwined with the identity and economy of the region yet fraught with danger.

The immediate aftermath revealed a glaring absence, a lack of a dedicated mines rescue or recovery team. Over the ensuing months, these individuals embarked on a gruelling mission to retrieve the bodies. It took several months to pump the water out of the tunnel and to clear the debris before the seven miners were removed, with the last body, that of Thomas Wright, being removed on the May 16.

The community rallied around the rescuers and the bereaved families. A widows and orphans fund was established, supported by contributions from within and beyond the mining community, a collective effort to provide financial and emotional support to those directly affected by the tragedy.

The presentation of addresses to the rescuers, crafted by D.F. Edward of the I.X.L. Company and captured in photographs alongside a memorial collage, serves as a tangible recognition of their valour. These gestures of appreciation, set against the backdrop of a community grappling with loss, highlight the profound impact of collective action and the enduring spirit of support and remembrance.

As we revisit the Eclipse Colliery disaster through ‘A Pic in Time’, we not only commemorate those who lost their lives but also reflect on the enduring legacy of the event. It serves as a somber reminder of the risks inherent in mining, the importance of community solidarity, and the need for continuous advancements in safety protocols.

We honour the memory of the fallen miners and the bravery of those who ventured into the depths to bring them home, ensuring that their legacy is not forgotten but serves as a catalyst for positive change in the mining industry.

| A special thanks to Ray Smith, General Manager of Operations with the Queensland Mines Rescue Service in Dysart for all the research information that informed this article. |