Mount Mulligan, a remote and rugged outpost approximately 170 kilometres west of Cairns in North Queensland, holds within its sandstone escarpment a chapter of Australia’s coal mining history.

The town of Mount Mulligan was first laid out in 1912, but by 1958, it was abandoned, leaving only remnants of what was once a thriving coal mining community. Today, all that remains are a cemetery, a single residence that was once the hospital, a chimney stack, and the electricity generator, providing a haunting glimpse into the past.

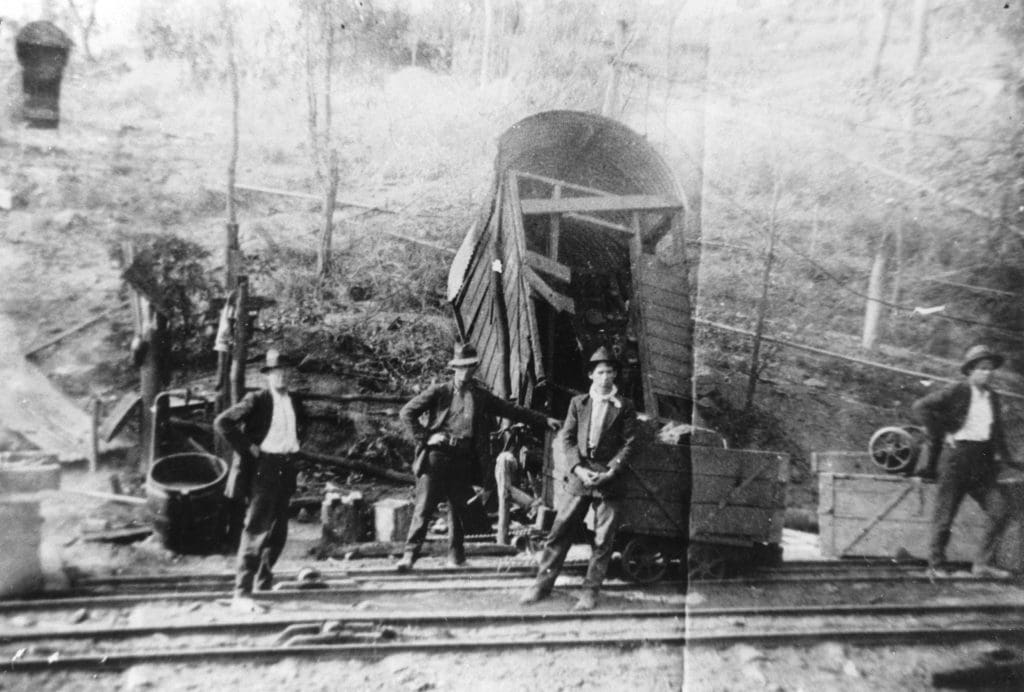

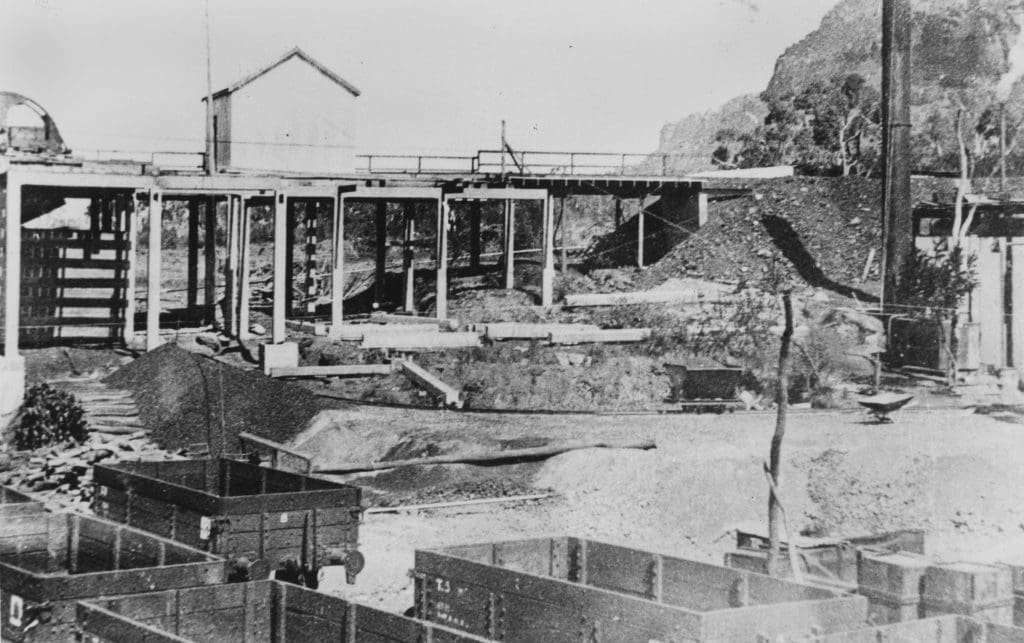

Coal was first discovered under the mountain in 1907, leading to the opening of the Mount Mulligan coal mine in 1915. This was no ordinary location for a coal mining town, Mount Mulligan’s isolation and its rough, mountainous surroundings made it a challenging and inhospitable place to work. Yet, the mine was essential to the Chillagoe Company’s smelters and locomotives, supplying much-needed coal in the far north of Queensland.

However, Mount Mulligan is forever linked to one of the darkest days in Queensland’s mining history. On September 19, 1921, the Mount Mulligan coal mine was torn apart by a catastrophic explosion.

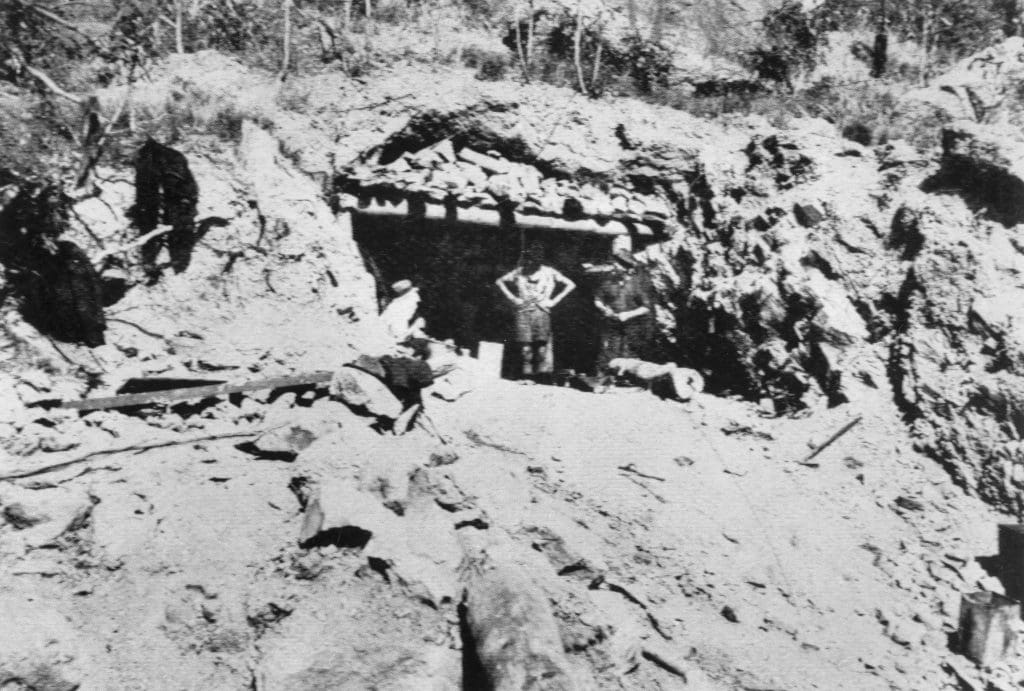

The blast killed all 75 workers underground, making it Queensland’s worst mining disaster. Coal dust, which had accumulated in the mine’s tunnels, ignited with devastating force, and the explosion was so powerful that debris was blown from the mine’s entrance and heard over 20 kilometres away. The intense heat and pressure caused by the explosion made rescue attempts difficult and dangerous.

In the aftermath, only two men were pulled from the mine alive and they succumbed to their injuries shortly after. As rescue workers dug through the collapsed tunnels, bodies were slowly recovered, with many miners identified by grieving family members. The town, which had gathered in shock at the mine entrance, was devastated by the loss, and Mount Mulligan’s cemetery became the final resting place for many of the miners.

The cause of the explosion was attributed to a combination of coal dust and an accidental detonation of explosives, as identified by the Royal Commission’s findings. The inquiry ruled out other potential causes, such as methane gas ignition, and concluded that an explosive, possibly placed on a large block of coal, detonated improperly, igniting coal dust in the confined tunnels. This lack of proper safety measures in handling coal dust was a key factor in the severity of the disaster.

Despite the disaster, the mine reopened in 1923 and continued operating until 1958. However, the shadow of the 1921 explosion lingered over Mount Mulligan and the town never fully recovered from the tragic event.

Today, Mount Mulligan’s eerie remains stand as a memorial to those who lost their lives, offering a solemn reminder of the dangers early miners faced in their pursuit of coal.

Although Mount Mulligan is now a ghost town, its historical significance and dramatic setting make it an evocative destination for those interested in Australia’s mining history. Modern visitors can explore the old township and the remains of the mine through guided tours that bring the past to life, allowing a new generation to reflect on the impact of mining in one of Queensland’s most isolated locations.

Information and photos for this article was compiled from the Mareeba Historical Society, Australian Mining Accidents (Mine Accidents Database), and Atherton Tablelands Tourism, as well as archives from the State Library of Queensland.

| For more information on tourism at the site, visit www.mountmulligan.com |

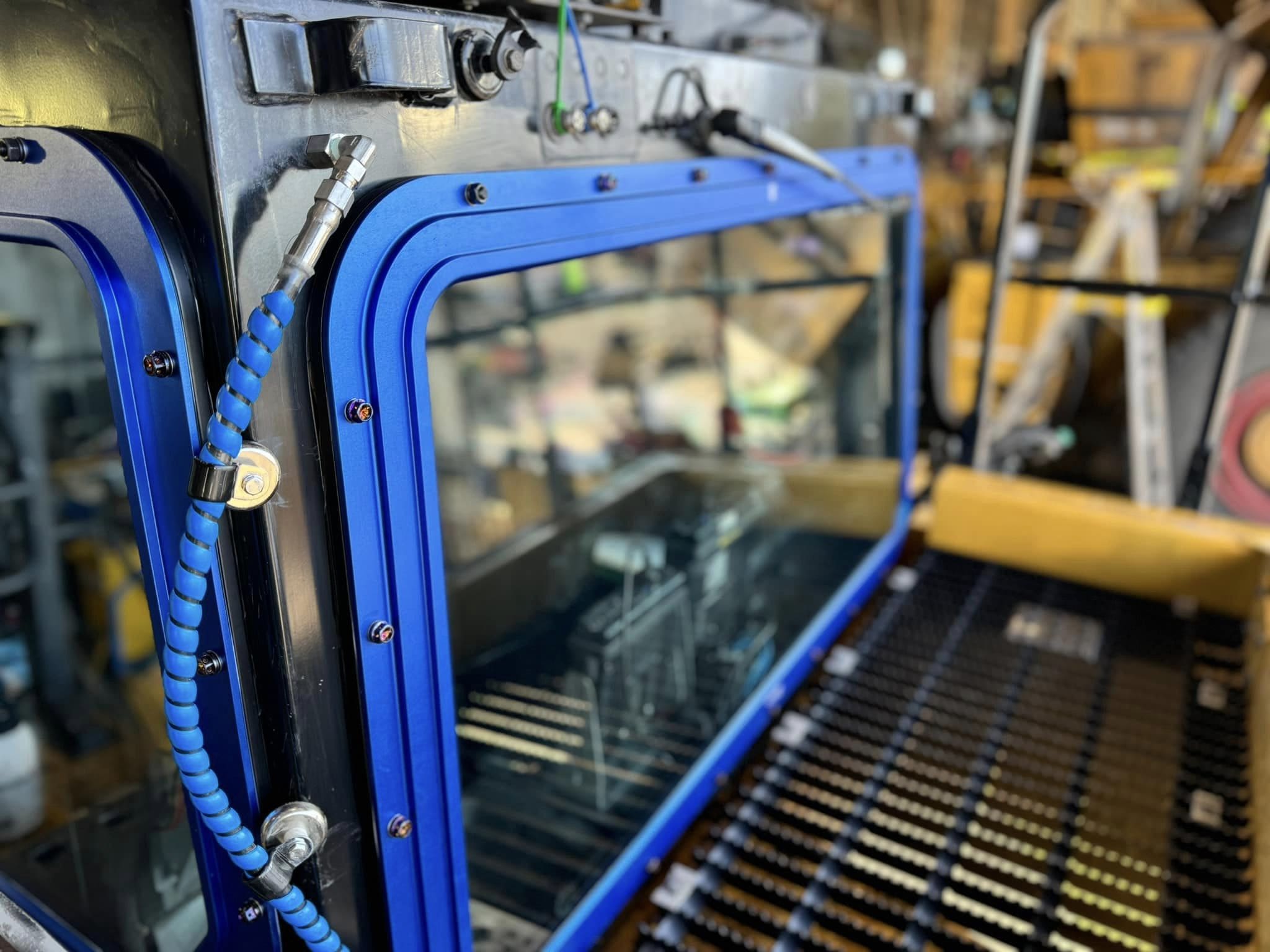

Header image: The cable drums were blown 50 feet from their foundations by the force of the explosion.